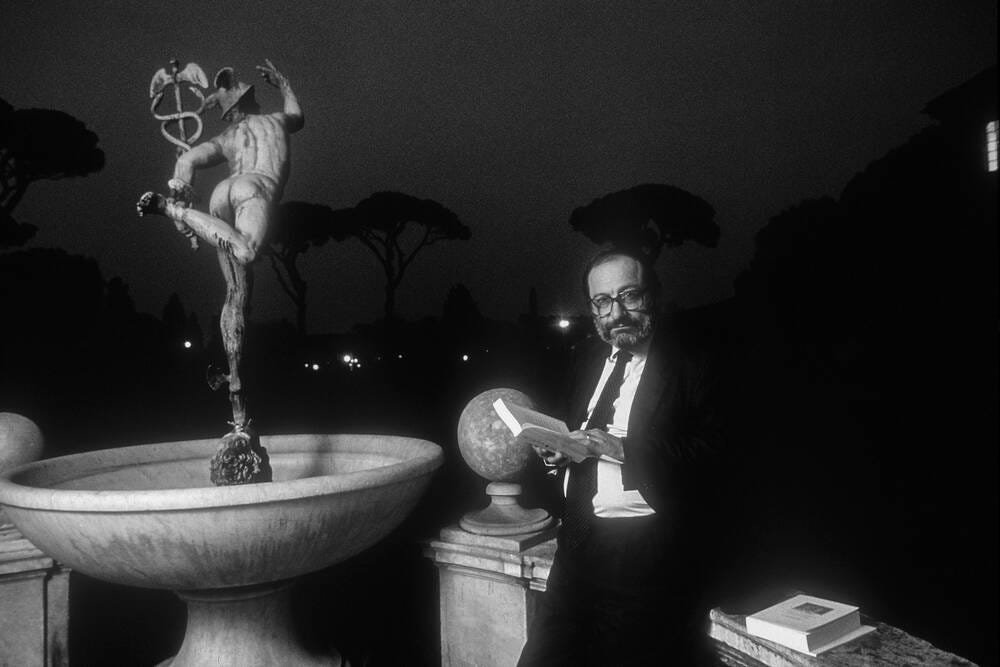

“Perché i libri allungano la vita”.

By Umberto Eco - 1991

Friends,

There’s more than one reason why learning multiple languages expands our ability to communicate what we think we need to say, and to understand what is communicated to us.

If I say something in my mother tongue and then say it in another language, I might lose weight; it may come out “wrong” as easily as it could elevate the entirity of the sentence.

Most of the time, when going from a Germanic to a Romance language, the way we build words shifts from a compounded word to a prepositional phrase—which is, quite literally, dismantling one word into several, and therefore into several concepts: more words to express “one thing.” This might seem obvious to some and interesting to others, but for me it has always carried a feeling: that there is almost always a better way to express something with more accuracy and precision—or, when you need to, to be vague and ambiguous. To shape an amorphous feeling into a poem, the intangible anger of an injustice into a letter, or the greatest of sorrows into a wonderful song.

In any case, I do these translations of texts that don’t have one, or when I don’t like the ones I’ve found—sometimes as a way to study them, and most of the time for my own amusement. It could very well be translating an essay from English into Portuguese for a friend of mine, or an excerpt from a book about Christianity written by an atheist historian, which I send to my mother so we can have a conversation about it later—so that someone I think might benefit from reading it can access it.

I’ll start sharing these here. This one is from Italian to English: a wonderful column by Umberto Eco—one that every internet friend of mine should read once in a while.

Why Books Prolong Life

Not long ago I amused myself by imagining those ancestors of ours who spoke about their slaves trained to draw cuneiform characters as if they were modern computers. I was amused—but I wasn’t joking. When today we read articles worried about the future of human intelligence in the face of new machines that are getting ready to replace our memory, we sense a family resemblance. Anyone who understands the subject a little soon recognizes the passage from Plato’s Phaedrus, quoted countless times, in which the Pharaoh anxiously asks the god Thoth, inventor of writing, whether this diabolical device will not make man incapable of remembering and, therefore, of thinking.

The same reaction of terror must have been felt by whoever first saw a wheel. He must have thought we would forget how to walk. Perhaps the men of that time were more gifted than we are at running marathons across deserts and steppes, but they died earlier—and today they would be discharged at the first military district. By this I do not mean that, for that reason, we should stop worrying about anything and that we will have a fine, healthy humanity accustomed to having its snack on the grass in Chernobyl; if anything, writing has made us more skillful at understanding when we ought to stop—and whoever does not know how to stop is illiterate, even if he rides on four wheels.

The uneasiness produced by new ways of capturing memory has always existed.

Faced with books printed on poor paper—which gave the impression they would not last more than five or six hundred years—and with the idea that such books could already be in everyone’s hands, like Luther’s Bible, the first buyers spent a fortune having the initials illuminated by hand so that, thanks to that, they could feel they still possessed parchment manuscripts. Today those illuminated incunabula cost an arm and a leg, but the truth is that printed books no longer needed to be illuminated. What have we gained? What has humanity gained from the invention of writing, of the printing press, of electronic memory?

On one occasion, Valentino Bompiani circulated a phrase: “A man who reads is worth two.” Said by a publisher, it could be understood merely as a happy slogan, but I think it means that writing (language in general) prolongs life. From the time our species began to utter its first meaningful sounds, families and tribes needed the old. Perhaps at first they were of no use and were cast aside once they were no longer effective at hunting. But with language, the old became the memory of the species: they sat in the cave, around the fire, and told what had happened (or what was said to have happened—this is the function of myths) before the young had been born. Before this social memory began to be cultivated, man was born without experience, had no time to forge it, and died. Afterwards, a twenty-year-old was as if he had lived five thousand years. Events that occurred before he was born, and what the elders had learned, became part of his memory.

Today books are our elders. We do not realize it, but our wealth compared to the illiterate person (or to the person who can read but does not) lies in the fact that he is living and will live only his own life, while we have lived very many. We remember, alongside our childhood games, Proust’s; we suffer for our love, but also for that of Pyramus and Thisbe; we absorb something of Solon’s wisdom; certain windy nights on Saint Helena have shaken us; and together with the fable our grandmother told us, we repeat the one Scheherazade told.

This may give someone the impression that as soon as we are born we are already unbearably old. But more decrepit is the illiterate

person (by origin or by relapse) who suffers from arteriosclerosis since childhood and does not remember (because he does not know) what happened on the Ides of March. Naturally, we might also remember lies, but reading also helps us to distinguish. Not knowing the faults of others, the illiterate person does not even know his own rights.

A book is life insurance, a small anticipation of immortality—backward (alas!) rather than forward. But you can’t have everything instantly.

(This translation was produced without the use of AI.)